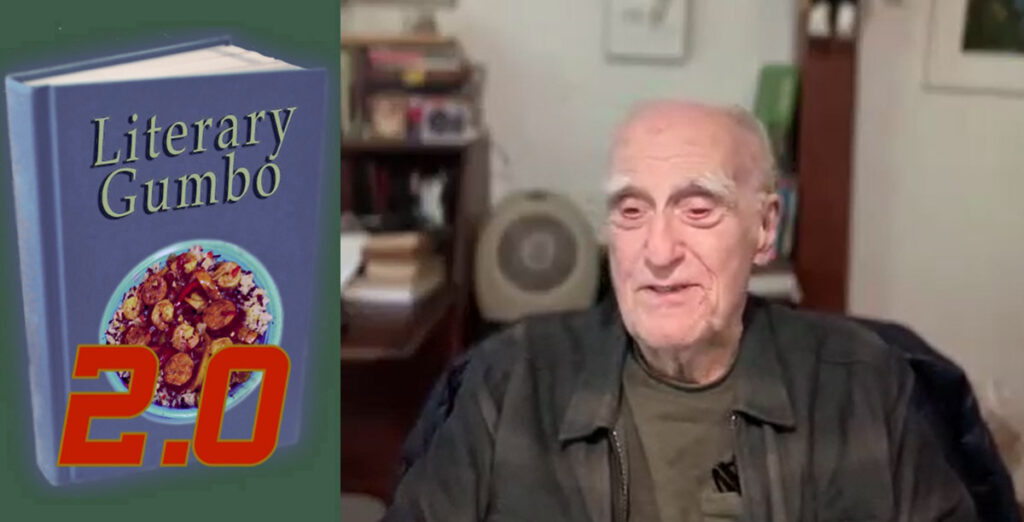

This is the last episode of the first season of Literary Combo 2.0. I’m looking forward to season two, but this first season I’ve dedicated to the memory of the original host of the Literary Gumbo talk show, Fred Klein, who had a very long and illustrious career in traditional New York publishing, which looks so completely different than today. So I wanted to explore how publishing has changed over the last 50 years. To do that, I came up with the perfect guest for today, everybody’s favorite writing guru, Shelly Lowenkopf. Welcome, Shelly.

Shelly: Well, thank you very much, Lisa. And of course, you start right off by mentioning one of my oldest friends and connections in the publishing industry, the late lamented Fred Klein. And when I first met him, this is an interesting story. I was at the time the editor for a publisher out of Los Angeles. And we were we were a general trade publisher trying to make our way.

And basically we were relying on sales, you know, losing the paperback rights to publishers like Bantam and Dell and New American Library. And so I had a couple of close associates in Bantam and there I was with a project under my arm. And I was thinking, well, maybe I’ll pick up a commitment from Bantam and I hear this sound coming from down the hall and it’s sort of a bellowing calf.

And the person who overseeing them says, Oh, don’t worry about that. That’s Fred Klien. He always talks like that. And before our last meeting, I had to go down and introduce myself and said, Fred, you probably don’t know me, but. And you know the rest of it because how many times in your memory did you pin the microphone or my lapel when I was on Fred’s Literary Gumbo show?

But that was the beginning. But to get directly to your subject also at that time, let me start with this little bit of background. I got into publishing by complete accident.

All I ever wanted in life was to be a writer.

And that was my goal, my ambition. And I saw something. I saw nothing more. And basically that led me to the other side of the table, as it were, before I got this particular job, which launched my publishing career, which was way back in early 1970s. Can you go back that far? And I had a friend from the Thursday night writer’s poker game he was born in Chicago with the name of Gunner Jarvis, and he changed his name wisely enough to day in day like any.

And he sort of dropped this little bomb on me and said, if you really want to make it as a writer you’ve got to develop your chops. In the easiest way to do that is to write a novel a month. Oh, okay, no problem. And I did. And then I said, So. Okay. Couple of months after three or four months, I got screened for novels and said, Well, now the trick, of course, is to sell.

And that was the next step. And in the process, I found a publisher of magazines and journals in Los Angeles who got into the so-called paperback revolution. And he hired me. He said, I have a list of books here. And how long do you think it would take you to write, or how many of these do you think you can write?

And I, of course, scanned the list and pretended to read. There are no problems. I can write all of them because there it was again an opportunity to pay the rent every month. So I was writing a novel and a work of nonfiction every month. And at the time, it was indeed possible to make a living, if not a respectable living, at least enough to pay the rent.

So in the course of that, the publisher who I was writing the nonfiction books for Salamander, was often said, You know, I appreciate what you’re doing, but the time is right and I need more product. You must have some friends who are writers. I said, Sure. Thus, that was my first step into becoming an editor, calling Francine and saying, Hey, I’ve got a gig here for you if you can handle this.

And after a time the publisher said, Let’s get serious because you are in New York. And that’s where his background was. And he then hired a friend who was a sales manager at Grove Press, which was one of the icons, one of the early hard cover publishers of material that they approached not mainstream, but certainly sold today on eBay for big bucks.

And so in comes a guy by the name of says you guys are doing this all wrong. We got to get things going here. And first and foremost, surely you’ve got to have an office. You can’t just keep coming in here and hang around, so we’ll get you tarred better and put you over here.

Oh, and by the way, I’m putting in for a subscription to Publishers Weekly. You got to find out what’s going on in the industry. And after about two months, he said, okay, now I’m getting your subscription to the Library Journal, because, as you will quickly see, that’s where most of our sales will come from, libraries. And at the time, this was a big deal.

If a hardcover book was taken around by, say, the Brooklyn Library or the Manhattan Library, that alone would pay for the production of the book. And so that was almost a guarantee of some kind of breaking even or profit. Well, that’s how it was at the time. But also because of taking Gunnar Keirstead, who introduced me to his agent, Donald MacCampbell, who at the time was known as the king of the paperbacks.

And so MacCampbell took me on as a client, and he said you’re no longer going to have a problem selling these books you write every month. But while we’re at it and this is how publishing was also at the time, MacCampbell said, By the way, I’ve been working on a memoir. Any chance you would be interested?

So here it is. And probably I am the first editor because I didn’t consider myself really an editor. Then I just fulfilled a function and I was certainly trying to develop my chops and get more and more experience and reach. But sure, I acquired Donald MacCampbell’s memoir, and indeed, you could still find it on eBay. And I think I even saw it not all that long had gone on Amazon and the title of it is Don’t Step On It—It Might Be a Writer.

Lisa: Yeah, that’s right.

Shelly: MacCampbell certainly had that attitude and he well, I kept getting writing assignments for him. But after a while, it began to seem like I could make a living as an editor. And so I cut back on my writing output and spent a lot of time reading books, talking to people that I knew and trusted.

And by the way, I’m going to drop another name for you and somebody who might be a good person to do an appear. I have a pretty tight friend here in Santa Barbara by the name of Max Talley. His father worked for new American Library and that I kind of wanted to be I sort of saw as a role model.

His name was Edward, or his nicknamed Ned Chase. And that’s one of my connections with Mac I knew and admired Ned Chase. And his father was an editor for Ned Chase, who was the editorial director of New American Library and it so the subtext here is, is contact being in the publisher industry. One got it made in one direction.

No other editors because when write in the process of my first job as an editor, one of the paperback editors I saw in New York was her name was Agnes Birnbaum. Well, she was the editorial director of a small paperback publisher. And I sold, you know, so I think I leased some of the rights to the titles I had published here in Los Angeles.

And after a while, as soon as change sometimes happens, Agnes got tired of her job with the small publishing company that became a literary agent. And one of the first things that happened was she said, I know you’re not happy with that. But MacCampbell, he keeps throwing these awful assignments at you. I think I can do better. And so in a sense, yeah, she poached me away from MacCampbell.

But the point is that it was more or less like a fraternity. And indeed, as I said in the beginning, all I wanted to do was be a writer and make my living that way. However well that went. And finally, the deal was that at the time I had been fired away from my job with the right publisher to run the Los Angeles office of an organization that was then called Dial Delacorte Press, my rival.

And this goes back in a way, to my association with Fred and some of the great people at Bantam. My rival was a guy by the name of Charlie Bloch, who ran the Bantam office in Los Angeles. One day Charlie calls me for coffee and we’re talking. And he said, Listen, you’re going to do me a favor.

We’re having our sales meeting and I’m going to be out of town for a couple of weeks, maybe three weeks. And I would really be grateful to you if you would take my courses at USC and teach them in my absence. So what I have done here in years is conversationally. And what kind of mountain goat leaps of logic.

So is it show the accidental or distractions from my real purpose of writing. You know, first becoming an editor and getting to do no other men and women who are in the publishing industry and then as a teacher, because after taking college classes, there was a graduate program at USC called the Professional Writing Program. Which and USC almost most universities make the distinction between a program and a department in a program the faculty does not have to have a Ph.D. does not have to worry about tenure, track or any of that sort of thing.

And so, okay, the head of the department at the professional writing program called me in after Charlie came back from the sales manager sales meeting and wanted to get back to teaching again. The German emcee of a successful screenwriter called me in to his office and said, Listen, the students are threatening armed revolt if if, you know, if you don’t come back.

So promise me that I can rely on you to teach your course next semester. Sure. What the heck it’s income. Why not? The thing that rankled me then and even to this very day, in a sense rankles me, is that I was a graduate that made the university across the city from USC, and we were in a kind of bitter rival to sort of like the rivalry between, say, Duke and the University of North Carolina.

And it always rankled me that I had never been invited to teach it at UCLA, rather at USC, where it became a kind of institution that lasted for 35 years. And indeed, in more recent times, like around, you know, to 2010, 2012, around here I was teaching and in another interesting program at UCSB. And every time I drove on that campus, which I have to admit is a pretty attractive college campus, I’ve been on college campuses before, and that’s with the possible exception of the University of Nevada, Las Vegas.

They’re all beautiful. And that’s just sort of well, that’s a lot of stairs. But every time I drive onto the campus at UCSB, the first thing that comes to my mind is this isn’t UCLA. It kind of rankles. But to get back to the subject then when publishing and teaching were distractions from my goal of wanting to do nothing but writing and the way I want to tie that up is to suggest this, Lisa, that it is my belief now

things have happened in publishing and have progressed and not necessarily for the good, but not necessarily for evil either.

But publishing has changed and it is no longer that easy for an individual to make a living as such in publishing. And that also includes editorial salary. So some publishers pay fairly well, but not outrageously. There are better ways if income only is an issue like, say, plumbing or carpentry or even being a pizza chef.

But that being said, there are more and more small publishers. The big thing at the time I fell into the industry and began making friends. Well, had to do with the seasonal list in the catalog. And every publisher was working this is why in a lot of cases you send a manuscript to a publisher and you don’t hear anything for a month, two months, three months, because the editor and the sales manager and everybody else is busy putting together the catalog for the coming year.

And the larger publishers would have, you know, 30, 40 books a season and the smaller ones would have, say, eight or ten a season, meaning, you know, more than than ten books, 20 books a year. And then the smaller publishers would publish maybe five or six books a year.

But now there has been a proliferation of smaller publishers.

And here we go with the letter situation. At the time I got into publishing, there was a term the publishing industry equivalent of the N word, you know, in common conversation, and that would be vanity publishing. Yes, that’s what it was called. Oh, she’s published by a vanity publisher, meaning, you know, and now through euphemism, it’s self publishing.

And indeed, I have known people who have done quite well with self-publishing, and there is nothing but generally good in both the product they produce and the service it provides, but largely and this in a way, there’s an interesting equivalence now as the introduction of artificial intelligence into our life and culture is made. If self-publishing is a factor and it’s not going to go away.

And in fact, it wasn’t all that long ago when I even had an occasion to crow the very same Max Talley I mentioned to you earlier, and I said, Do you have an accurate definition for this term hybrid publishing? I have an idea what it means, but I want to hear what you think because I think it means self-publishing.

And he more or less agreed with me and I said how do you square the fact that you, as a workshop leader and a participant in the Santa Barbara Writers Conference include that is a part of the menu you offer for people and you know and galleries aren’t your I think it just goes right straight to the point he said well because it’s a reality and people need to have a choice.

So what I’m about to say now is, is my opinion, it’s the way I see it. And I’m simply here being responsive to your goal here of getting me to talk about some of the changes in publishing and what it involves is this It’s a shift game of the risk factor. The hybrid publisher has shifted the risk.

The financial risk to the writer.

Most self-publishing publishers are hybrid publishers, but don’t lose money because their income, yeah, is affected by sales, but it is not adversely affected by sales. Which is to say that in most cases the writer bears the cost. The risk. And back in the day, one of the things you one of my early jobs is as a publisher and an editorial meeting, there’s a particular project I’m really plumping for I want to publish.

And I think that this book has merit and that there’s an audience for it and that it’s going to do all right. And I also have in mind some of the, shall we say, the benchmark is an important benchmark paper printing and binding. How much is that going to cost?

Lisa: Yes.

Shelly: You’re aware of that. And then there’s another one which is the author is royalty too, because at the time I was first involved with publishing the standard royalty went like this for a hardcover book. The first 5,000 copies of the book actually sold. The author gets 10% of the cover price, right? And then if it sells an additional 5,000 copies, that goes up to 12 and a half percent.

And then if it sells the 10,000 and all subsequent copies that are sold, the author gets 15% of the sales price burn off that they don’t that’s equitable some might say that is not. But that works out pretty well particularly when you consider that even today and even in the case of self-publishing and whatnot, let’s say that you and I have books.

Well, of course, in fact, we do. But we well, we take our book to a place like Chaucer’s and say, okay, will you stock my book? And the discount schedule. There is 40% off the cover price. So a book that would sell for $10, I’m using that just because I’m awful at math in my head and I can I can mess with that.

But a book that would sell for $10 at Chaucer’s would pay four dollars. And so the publisher then would get in theory that remaining $6 from which they had to pay the author and amortize the cost of paper printing and binding plus there’s this wonderful weasel word called overhead. See? And at the time I was involved, my first experience in publishing, which was based in Los Angeles, it became really important and financially feasible for us to have a warehouse to store our unsold books or books that were about to be delivered in Nevada.

So Sparks, Nevada. Why Nevada? Because California has an inventory tax. You didn’t know that? Well, yeah, you have to pay X percent on every year on an inventory, whether it’s books or sausage or anything else. And also in California, things in storage in California had then an unpleasant habit of being invaded by things like mice, which is what Fred had a great term for books that mice had gotten to. Those are hurt books that have been hurt by the mouse bites because they could be sold well. Okay. Those are all factors that cut into the publisher’s ability to gain anything back. And I remember giving this example of a particular book I wanted to publish. The publisher stopped me and he said, and again, this is historically sensitive. Interest rates in banks and whatnot were somewhat different than they are now.

But what he said to me was, okay, we’re looking at about 40 or $50,000 that it would take to do, you know, give the rancher an advance and pay for things like typesetting and promotion and all of that. You’re saying that if I turned 40 or $50,000 and put it in the bank and bought a certificate of deposit for six months, that the sale and the ultimate sale of this book would bring me a greater profit, which is one of the things editors have to learn.

And if they don’t read it, they need to get another job someplace else. The other job they get is as a literary agent. But this is what I meant when I say that, that the heritage publishers, the standard publishers, bore the financial risk. And that’s the whole concept of arrangement. Your financial arrangement between author and publisher.

Most contracts. And for most of the publishers I work for, in fact, with that very culture, bear in mind I have a contract that says that if there are subsidiary rights sold, the publisher gets a piece of the action. The company I work for in most hardcover publishers ask for an auction, got 50% of the income. If a title was sold.

It was reprinted as a mass market paperback or even what we call a trade paperback. And then another important allied and subsidiary write had to do with motion picture sales. And we would get a small percentage of that. And remember also, Lisa, that most American contracts with traditional publishers say in as many words, the author has first English language rights or North American rights write in the following project meaning that there is a possibility for added income in in French, Spanish, Italian, German and Japanese, Chinese.

So this term allied and subsidiary rights. That was also part of the algebra that an editor has to be aware of in the traditional sense. Now, another interesting thing too, because publishers are always busy doing what they do. It’s how much time do they spend with acquisition and how much effort do they put into it. And just as briefly as I can tell it right now, because I know we’re on an hourglass here, here’s an example of how this works.

There is still a publisher who had a very reliable writer his books sold fantastically well. Some of them were made into movies. There was no trouble selling his book, his name was, and he was a really good writer. Larry McMurtry. So to show you how the information and intelligence, the action in publishing works, the word is and somebody McMurtry’s publisher gets the news.

McMurtry has gotten on a plane in Dallas and he’s flying to New York with his new novel. And unfortunately, it’s a thousand pages, which means it’s going to be it’s going to be expensive. And then somebody else adds to it and says, Oh, we had a brief chat with him and unfortunately, it’s going to be a Western.

Well, okay, this information was in hand before McMurtry even dropped in New York before the plane landed and the decision had already been made. He we owe him. We’d made money from him. He’s a great addition to our list. He’s got a great future as a writer. So here’s what we will do. We will give him a medium sized advance, which is to say, an interest free loan on potential sales.

And we will commit to publishing 3,500 copies of the book and we’ll write it off as a loss, because a book that size and one string in today’s market can’t possibly sell. But there, of course, is the clause in his contract that says we get first look at his next book and his past books have done well. And this is, you know, and all right, this is giving him a chance.

He wants to write a Western. Let him write a Western. Okay. They had no idea what they were getting into because, of course, the book and you probably guess this, Lisa was Lonesome Dove, which is still selling copies, which shows in many ways how much publishers really know when you come down to it. So, you know, in an attempt to tidy up this business, I’ll say this, that one of the reasons self-publishing is so popular is because a lot of people who want to write, who are concerned about the quality of writing and who may in fact even think that what they have their project has some literary merit or worse or lasting value, or do impatient and too frustrated by not getting answers or by being put on hold. I had a student and in fact, maybe you even know her because I think she’s come to the writers conference a couple of times and she’s from Ventura. It took her something like, oh, four or five years to get a novel. And she was working on in a condition where a publisher wanted to publish it.

And even then, after the publisher said, Yes, we will publish it. And then there was the process of editing and copy editing and all of that. It was 18 months after the agreement was signed, before she hefted an advance copy of the book in her hand and some people are really too impatient and too frustrated. And of course, they sent things.

They send a query letter to an agent and sometimes they don’t hear for a month or six months, or sometimes they never hear. And so it’s like that play on her. And she heard that TV series Orange is the New Black. No comment or no answers is the new No. So naturally they go to the so-called hybrid or self-published venue where indeed they are told, oh, we can do we can handle this.

Oh yeah, we love your book. But in so many ways, these hybrid or self-publishing venues do not have connections for distribution. And so it becomes up to the author, literally driving around with a station wagon filled with copies of the book going from bookstore to bookstore. You know, you start here and then you go to L.A. and then you drive to San Francisco or maybe Denver.

And of course, there’s Portland and Parallels books and then there’s Seattle. And it puts more of the work that the traditional publisher does. And they’re responsible. They wanted the author, and I would say 80 to 90% of the risk.

Lisa: I’ve been ticking off a lot of what you were saying as far as all the different changes that we see now and it’s like starting with that, when you first started, they said, oh, okay, we got to get you an office, we got to get you in here, which is something that we see today. We read about how publishers, whether they’re in New York or no matter how big they are, they’ve got these people who hardly ever come in to the office once a week, but most people work from home these days in business.

Shelly: And indeed you take that one step further. They set up some of these people in hybrid or self-publishing. Can sit or there’s a side hustle. This is not their entire source of income.

Lisa: Yes, there’s got to be a lot of different things. And then there’s a what you’ve talked about paper. You talked a lot about things that come back to paper and how much paper you must have dealt with over the years as far as even probably just starting with typing something with carbon paper.

Shelly: Oh, yeah, absolutely. You start one of the big sounds I still hear in my ear and think about fondly. And it just reflects the change in technology. When I first started, it was a series of some typewriters, in some cases standard typewriters or portable typewriters, and then one at the appropriate time in my life, my father was working for an auctioneer, auctioning off the businesses that went bankrupt or some kind of failure.

There were always typewriters around.

So I never really had to buy a typewriter. And then indeed, a deer jumped in the university. It gave me a wonderful typewriter that was all very portable. But what I’m getting at is the sound, and then you evoke that when you read it. You said that word that really sets the sound, the ear ratcheting when you pull a sheet of paper out of the platform of the typewriter, and then you wad it up, and then you toss it to a nearby wastepaper basket.

And here’s something else that has changed in the publishing industry, because I remember vividly, I had a gift from my cherished big sister. It was an oversize wastepaper basket, that came with the pattern on it. But very quickly that became covered with rejections. So where I write based on the rejection slips, you’re rubber cement on the wastepaper basket.

And it was covered. It was just there that was learned of the bit you try to manuscript. You put it in an envelope. You went to the post office and send it off. And of course you had return postage so they could send the manuscript back. And more often than not, it came back with something the size of a small snapshot and say we regret your information, your material was not found acceptable or words to that effect.

And now that’s pretty much gone. I remember I used to take a huge manila envelope filled with rejection slips and dump them on the desk and say, Anybody know what these are? And look at your order. I said, Well, your grade depends on it because it was I can see that you’ve gotten five or six of these.

You’re not going to get anything higher than to see meaning I want you to be sending stuff out. Well, now the rejection slips are e-mails, but almost invariably you’re again, talking about assigning your risk to the publisher. You know, we look to see more of your work and we’ll be happy to do. But I want to suggest you subscribe to our magazine.

And in future, you know, let us know if you’re a subscriber we will read your manuscript sooner. Okay. So it’s all right, I think somewhat, but not entirely facetious about it, because individuals come along and in our way. Lisa, I have to point my finger at both you and me, because this is one of our one of our hazards to we consider ourselves in other terms.

And yes, I agree entirely. And you know, from past experience that I’m well aware of your editing experience, and I know you appreciate mine, but a lot of people call themselves editors. And what they mean is that they’ve got an A in grammar.

Lisa: Oh, yes. They say that if you want to find a good editor, make sure you don’t get an English teacher.

Shelly: Yes, absolutely. Oh, that’s the worst kind. Because one of the great things we both learned is that you don’t need complete sentences when in fact sometimes complete sentences are way too formal and in due date, former student of mine just had an experience with a literary agent that you and I both know. And being the literary agent we share.

Why are you sending me people who are so formal using complete sentences and all of that. Well, yes. So it is in a way,

I believe in the jungle that publishing was in the beginning when I started has transformed. It was a friendlier jungle. But there are all kinds of people who are angling around now and interested in making sure that their efforts don’t go unrewarded, meaning there’s a payment up front.

And my it’s a kind of rhetorical question about what you write. You’re supposed to deal with this when a writer is probably managing you, you’re just barely managing to be able to do what they read in Internet bills to keep the computer going in order to be able to send letters and manuscripts to very well wishers. And we were the agents writing most books most in trade publishing, by which I mean books, hardcover, paperback, trade, paperback are sold in bookstores, in the newsstands.

And of course, sometimes through mail order, through Amazon and Abebooks and other platforms. But trade publishing is distinguished by the fact that in any given year and certainly in this particular century, we’re getting close to having knocked off a quarter of this century already. But as far as this century is concerned, the average novel sells 500 copies or less.

And that goes back. That includes, by the way, the so-called heritage or brick and mortar publishers, the Simon and Schuster publishers and whatnot. And there are all kinds of interesting deals. And just to show you how this works here in beautiful downtown Santa Barbara, and this was back toward the end of last year, I think would have been around October of last year.

I had a deal, an arrangement with our local bookstore, Chaucer’s, because I had a book coming from the Berkeley imprint of the the Random Penguin family. And I was even given an evening and a book signing and you can talk about your books and read the first chapter and then a box arrives.

This usually happens from publishers with authors copies of the book that I see and printed across the cover. It’s for sale only at WalMart.

Lisa: Oh, no.

Shelly: Oh, yes. And that’s part of the deals that publishers are making now. So Michael Johnson says, I can’t let you in this store with a cover that says available only at WalMart.

So much for that and there it is. But by the same token. Yeah right. He said a quick note to the editor on Friday. She said, well, do you have any idea what Wal-Mart’s first order read your book was? No. She said, Well, would you believe your first order for the whole list is for the whole chain?

But they ordered 25,000 copies in a bar variation. Well, that’s certainly true, but my papers are paper printing and vinyl booted. And she said, Oh, boy, will it ever end. And if it does well, they’ll order another 25,000. So they’re JP In Hanoi, some kind of big gamble by excluding other possibilities or other sales platforms. But that’s another one of the changes that have happened in in traditional publishing.

And the difference is they the traditional publisher, is aware of that and basing a lot of their go or don’t go decisions on it, which is why in a sense, you have to look to writers such as I’m thinking Jane Smiley, because I’m so fond of her work, or Louise Erdrich, who, if she wants to get a Nobel Prize pretty soon, there is no justice in the world.

We know there are books are outstanding and literary quality, and they can pretty well do whatever they want. So that’s not even a question or an issue.

Lisa: So you’ve got the book that’s available at WalMart. You know, you’ve also have dealt with small publishers with your The Fiction Writer’s Handbook.

Shelly: Oh, yeah. And, you know, it’s different altogether.

That was different altogether because the place where that book was launched is one of my favorite bookstores of all time, and that’s romance. Yeah, I remember very vividly as a kid, at 13 and my father taking me in there and saying, This is what a bookstore should be. And right there I’m looking around and looking for titles that are recognized and I’m saying, No, babe, I’m going to have a book in here.

Well, it was true. But now small publishers have to work harder. And truth to tell a romance. In this particular case, their first order of book was ten copies. And so, in effect, the publisher knew all about this. So we both went to that with a carton of we bought them in our car just in case.

But here again, a nursery here is a carton of books. And I think there were something like 50 in there. And in order to filter it, to sell it, even though they didn’t buy it or order it in the first place, we had to give them a 40% discount because they’ve got to make that issue right too.

But there it goes, right back down to your question of risk. And in the in a way, Mark Twain, one of my favorite writers of all time, wrote a book that in so many ways informs my attitude, my literary voice, my approach to writing and to the right. That’s called the Innocents Abroad. The writer today, she knows exactly what’s going on in the world of publishing, is an innocent abroad and is likely to be taken in by.

There’s one particular editor I call him, and he comes out of New York, and I know it’s hit at least ten or 12 people here in Santa Barbara, He hits them for a $10,000 editing fee. And there’s no promise that the book is going to get published. I’ll do my best to make it count to the attention of people I know.

And again, to go back to that theme of they at one time at least the the closeness of writing. Well community, one of the people I met very early in my writing career was the publisher of a small New York publisher which called Stein, and they sold Stein and Patricia Day, a husband and wife. And from that point on, saw this being a very close friend and associate.

And one of his books, Stein On Writing, is the Bible for people who want to be fiction writers. And indeed, my copy of Stein On Writing, which was a gift from Sol himself, is from Shelly, the Energy who edits editors, because, yes, he used to pay me to read his manuscripts of his novels and leaps that you mention that one of my nonfiction books called The Fiction Writers Handbook.

There’s a blurb on the front cover from a dear friend, Reni Brown, who at one time was the senior editor, the lead fiction editor for W.W. Norton, one of the early and continued forces in literary fiction in America today. So it was a tiny group. And just simply to give you another interesting look on Fred Klein, you mentioned with such fondness when you began in the Literary Gumbo not that many years ago.

Of course, we still both in lived in Santa Barbara, but Fred and I and Mark Jaffe, the former editor in chief of books, were having breakfast. And Mark Jaffe is saying, you know, you are particular interest in mystery fiction or what not. We are starting a small publishing company, just the three of us. And Shelly, you and I would be the editors and I do all the paperwork, the publishing stuff, and Fred could be the sales manager.

And of course, my contribution know we call it OF books or old farts. Well, but again, it’s there. There is a kind of a closeness of people in in the industry. It’s still there and but it is more dispersed because more into visual arts or whatever their reasons for going to graduate programs in colleges encouraged by the way, incredible student debts to learn their way into writing.

And you know, in German some of the things that lady said I know you read every book on writing that’s coming out and you’ve got a great memory and you cite even the page where. MA It’s a particular game and I really admire that. But they also were using that as a way to get jobs in the publishing industry.

One of my better students at USC became a senior editor at the St Martin’s Press and remained in that position for several years and she couldn’t take it anymore and is now a literary agent. And it just this year most people who have been through the publishing process in the tradition in a way are, I would say, more stable and have a greater overall integrity and awareness of the publishing process and those who don’t work, who haven’t had the option of doing one of the things you do.

So well late summer, which is tracking the new books about writing and publishing and then digesting and then putting the work to use. Most time and again, there’s a literary agent you and I both know, and it’s one of her favorite job jokes for author is out there. I’ve got good news for you and bad news that, of course, the writers say, What’s the good news?

You’re getting published. All right. And what’s now what’s the bad news? You’re getting published and you sometimes you don’t realize until you’ve been through the process. Lisa, I know you’re not. You certainly know the difference, but how many want to be writers? How many people who have paid five or $10,000 to a self-published? You know, the difference between development and content editing and copy editing?

Lisa: That’s true.

Shelly: Not many. And I not least I know you’re know, because you even heard me telling the story at one point where a copy editor dinged me in a historical novel. And I mentioned somebody showing fuller brushes save for a brush salesman, and the copy editor sent a note and says Fuller Brush was not in operation at this time. So you’re really going to have to change that reference or change the timeframe of your story for accuracy. And of course, answer to that is I said, no, no, it was this was when Fuller was selling the brushes out of his parent’s garage.

And she bought it. She did that, which told me immediately, well, that one only saying told me something about her that she was quite a bit younger then than me. Because Lisa, you probably remember a radio program, two great Canadian comics, Bob and Ray. Does that ring a bell?

Well, they had a couple of fictional characters that that they used in some of their skits. One of them was named Wally Ballou. He was he was the incredible run of Chet Huntley and I’m sorry, of Tom Brokaw. And then there was Chet Sturdily, who was meant to be the governor under Chet Huntley. Well, I drew a character in this book, and I named him Chet sturdily and she didn’t question him.

It he let it go and we shot it. Just little, little things. We play little games. But the change is growing toward smaller and more independent venues. But I had this to say and this goes all the way down the line was the oldest publisher in America is still publishing their first publisher. The first publisher in America.

You’ll never guess what its its major title is, the For Dummies books, which shows how it goes from biography, autobiography and history to the For Dummies series.

Lisa: Yeah.

Shelly: Well, that’s one of the big changes. But there are a lot of small publishing ventures and they last maybe a year, five years, ten years. Well, there is still what Grove Press back in the day when I knew it, it was avant garde, you know, and political and somewhat sexual. And I knew Barney Rosset. They publisher very well.

There was a really wonderful publisher here in Santa Barbara when I first came. It was called Black Sparrow Press. He moved. He sold his home, in fact, in Santa Barbara and moved north because he made enough money on it so that he was able to buy a piece of property in Northern California that had not only a home but a storage building to store books and then eventually sold Black Sparrow Press to do another larger publisher.

So that’s still in the market. But bookstores, restaurants and publishers, the three business ventures or hustles that have the greatest risk and go out of business more often than not. And yeah, things are changing. I predict that there will be a lot more small publishers and a lot of these small publishers are going to do very well and be very responsible.

Who would have thought, you know, we’d think about publishing, We still think New York or Chicago, and certainly some of the university presses because they sell an awful lot of books. Right. So New Haven, which is for Yale University Press and Berkeley, of all places, which is where the University of California Press head office is located. But mostly when we think about publishing, we think, say, New York.

For a while we thought about San Francisco, and certainly we think about Boston, we think about the East. So who would have thought and let’s say you probably already know the answer and you, but you can look it up very easily. Who would have thought Minneapolis would have two real small, independent publishers today? They both do like ten or 12 books a year, which is to say the equivalent of one new book a month.

But they’re beautiful, they’re well printed, they’re well edited, they are well reviewed, they are well written. And so is it you know, is all of this stuff about hybrid and self-publishing and damaging only to those who don’t take the trouble to learn the the trade in the craft properly.

Lisa: That’s true because, you know, I’ve been contacted by people who say, can you help me promote my book? It’s up on Amazon. And I go, and do the look inside and read the first couple of pages and say, well, you know, first of all, you need to hire an editor. And so they know how to use a computer and Microsoft Word, they can just go take their manuscript and put it up on Amazon without any help from anybody else. That doesn’t mean that it’s maybe it’s a good story, but it needs work and need It needs help. And People won’t buy it unless it’s got that that polish to it. No matter how good a book marketer is, you can’t sell something that doesn’t have a good cover, that doesn’t have a good description.

Shelly: Yes. And that was another thing, too. When I first started in publishing, it was not just a tradition. It was an imperative. You wanted to be an editor. You had to work at least for the first five years on the job. You had to work two weeks a in a bookstore simply to get the sense of how people behaved in bookstores, what people were looking for.

And you’re mentioning and we said the cover is so important. And there are some artists who have made their name because of the book covers that they desire. And I’m thinking particularly of laughs. Noted and legendary book designer Chip Kidd. By now I have a great friend in Toronto whose designs are always winning awards in Canada, and one of my personal favorites, because she’s done a number of my books, is Deb Daly, who lives in Venice. But for the longest time, she was the design chief at St Martin’s Press. They have an idea of the philosophy and psychology of graphic arts. And you need all of this. It’s a dangerous and it’s a scary game, but it’s a playable game, a winnable game.

Lisa: Well, this has been a fascinating discussion and very educational, and I just I can’t thank you enough.

Shelly: Thank you for inviting me.